Infectious respiratory disease in dogs and cats is typically multifactorial, and syndromic qPCR panels now sit at the centre of rapid diagnosis, infection control and increasingly directed antimicrobial use. This post outlines key viral, bacterial and parasitic agents, and how qPCR can be integrated into everyday practice.

Overview of infectious respiratory disease

Canine and feline respiratory disease is usually a complex of co‑circulating viruses, bacteria and sometimes parasites, rather than a single pathogen. Large multi‑regional PCR panel data from 4,616 dogs and cats tested in 2019–2020 (Michael et al) showed that 44% of canine and 69% of feline samples were PCR‑positive for at least one respiratory pathogen, and coinfections were common. In dogs, Mycoplasma cynos and Bordetella bronchiseptica dominated, whereas in cats Mycoplasma felis and feline calicivirus were most frequent in that dataset. These findings reinforce that empirical “kennel cough” or “cat flu” labels often mask mixed infections with different implications for treatment and biosecurity.

Key viral pathogens and qPCR

In dogs, common viral contributors include canine parainfluenza virus, canine adenovirus type 2, canine distemper virus, canine respiratory coronavirus (CRCoV) and emerging agents such as canine pneumovirus (CPnV). Between 2019 and early 2020, CPnV prevalence in one large PCR panel nearly doubled (4.9% to 9.4%), and distemper virus also increased, while CRCoV detections fell, illustrating how molecular surveillance can track shifting epidemiology in real time. Recent work on rapid CRCoV assays shows that this virus is highly prevalent in high‑density settings such as kennels and shelters, underlining the value of fast qPCR for triage and cohorting. In cats, “classic” upper respiratory viruses remain central—feline herpesvirus‑1 and calicivirus—but newer metapneumovirus‑like agents have been detected molecularly and are being explored as contributors to feline respiratory disease complexes.

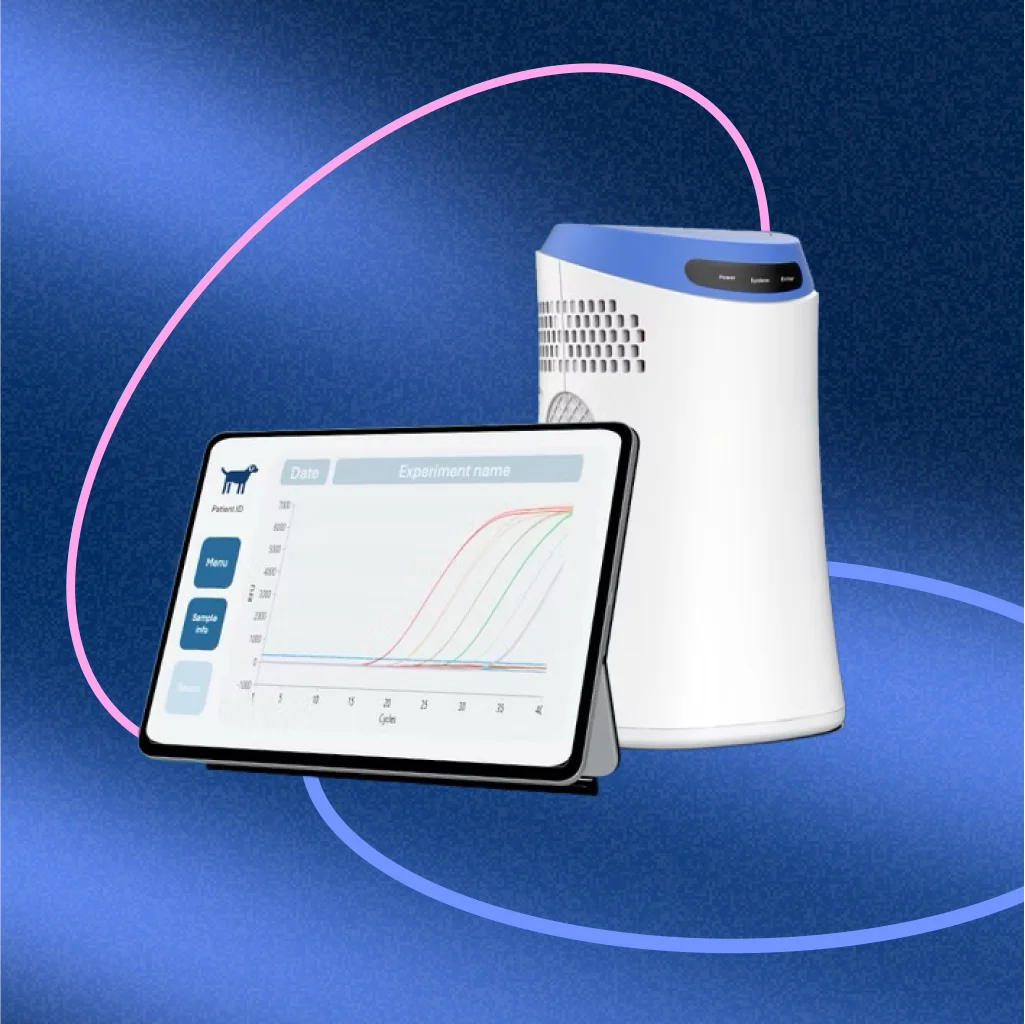

qPCR offers high analytical sensitivity for these viruses, often detecting low‑level shedding that would be missed by antigen tests or virus isolation, and multiplex designs allow simultaneous detection of several agents from a single swab. Turnaround times of 24–48 hours from combined oropharyngeal/nasal swabs are now routine in many reference labs, giving clinicians timely aetiologic data to refine therapy and isolation decisions. At Zytca Animal health, we have developed in-clinic PCR which allows for an even faster diagnosis, and turn around from patient assessment to treatment. Interestingly, large surveillance studies during early SARS‑CoV‑2 emergence showed that while human infections were common, none of >4,500 respiratory samples from pet dogs and cats tested PCR‑positive for SARS‑CoV‑2, supporting the view that routine COVID‑19 testing in pets with respiratory signs is unnecessary outside specific exposure scenarios.

Bacterial pathogens, AMR and targeted therapy

Bordetella bronchiseptica remains a key bacterial pathogen in canine infectious respiratory disease complex, often in combination with viruses such as parainfluenza or CRCoV. Mycoplasma cynos in dogs and Mycoplasma felis in cats are frequently detected on respiratory PCR panels and may act as primary or opportunistic pathogens, with coinfections particularly common. Syndromic qPCR panels reliably flag these organisms from upper airway swabs, allowing clinicians to decide when antibacterial therapy is justified and to steer away from unnecessary broad‑spectrum use when only viral agents are detected. In referral or ICU settings, coupling qPCR with culture and susceptibility from bronchoalveolar lavage or tracheal washes can refine therapy further, particularly in cases of secondary bacterial pneumonia or suspected antimicrobial resistance.

From an antimicrobial stewardship perspective, a negative bacterial qPCR in a dog with mild, self‑limiting cough dominated by viral detections supports a conservative approach focused on nursing care, mucolytics and, where appropriate, antitussives rather than default antimicrobials. Conversely, identification of Bordetella or Mycoplasma in a high‑risk dog (eg, brachycephalic, immunosuppressed, or with evidence of lower airway involvement) justifies targeted antibacterial therapy and intensified monitoring, and a positive mycoplasma result can guide the choice of drugs with good intracellular penetration. Re‑testing is generally not required for clinical cure, but in some high‑consequence environments (re-homing centres, breeding facilities), follow‑up PCR may be used to inform release from isolation.

Parasitic respiratory disease and molecular diagnosis

Parasitic lung disease is an important differential, particularly in cats with chronic cough or dyspnoea and compatible imaging, and it is easily overlooked if parasitology is not integrated into respiratory work‑ups. Aelurostrongylus abstrusus is a cosmopolitan feline lungworm that can cause severe respiratory distress; classical diagnosis relies on Baermann detection of larvae but is hampered by intermittent shedding and operator‑dependent sensitivity. A nested PCR targeting ITS2 rDNA was shown to reach up to 96.6% sensitivity and 100% specificity on faecal and pharyngeal samples, and it identified infected cats that were negative on Baermann or flotation. More recent field work from Brazil, using faecal and bronchoalveolar lavage PCR as the reference, found A. abstrusus stool PCR positivity in 74% of clinically suspect cats, while Baermann detected only 41%, with Baermann sensitivity of 56.25% versus PCR. Molecular confirmation of A. abstrusus has now been reported in domestic cats on multiple continents, including the first PCR‑confirmed cases from Africa, underscoring its global relevance. Feline respiratory panels and respiratory panels are available for rapid in-clinic qPCR at Zytca Animal Health.

For dogs, molecular assays are increasingly used for other lungworms (eg, Angiostrongylus vasorum, Crenosoma vulpis) on faeces or respiratory samples. Incorporating targeted lungworm PCR into respiratory panels or as an add‑on test is particularly valuable when diagnostic imaging suggests a parasitic pattern, there is a history of outdoor hunting or mollusc exposure, or standard kennel cough therapies fail to resolve signs. A positive lungworm PCR not only confirms the diagnosis, it also justifies specific anthelmintic therapy and follow‑up imaging, and may prevent unnecessary courses of other forms of antimicrobials. In endemic areas, combining Baermann with PCR (from faeces or BALF) offers the best overall sensitivity while allowing quantitative or semi‑quantitative assessment of worm burden and response.

Practical integration of qPCR into clinical workflows

In first‑opinion practice, a pragmatic approach is to reserve respiratory qPCR panels for animals with one or more of: severe or progressive disease, lower airway involvement, outbreaks in multi‑pet environments, poor response to empirical therapy, or high‑risk comorbidities. Collecting combined oropharyngeal and nasal swabs into appropriate transport medium or directly tested using in-clinic qPCR machines (such as the UlfaQ™ In-clinic Real-time PCR – ZYTCA | Advanced Veterinary PCR Diagnostics for Animal Health) maximises yield for both viral and bacterial targets, while separate faecal submission for lungworm PCR should be considered in cats and in dogs from endemic areas with compatible signs. At the population level, shelters, breeding kennels, rehoming centres, panel qPCR during outbreaks can rapidly define which pathogens are circulating, inform vaccination and quarantine strategies. .

For individual patients, qPCR results should always be interpreted in the context of signalment, vaccination history, clinical severity and imaging or bronchoscopy findings, since detection does not always equal causation, particularly for agents like mycoplasmas that may colonise without overt disease. Nonetheless, the accumulating literature over the last 5–10 years highlights that molecular diagnostics, when used judiciously, can shorten diagnostic odysseys, reduce empiricism, support better antimicrobial stewardship and sharpen conversations with owners about prognosis, contagion risk and the rationale for specific therapies.

REFERENCE:

Michael, H.T., Waterhouse, T., Estrada, M. and Seguin, M.A. (2021), Frequency of respiratory pathogens and SARS-CoV-2 in canine and feline samples submitted for respiratory testing in early 2020. J Small Anim Pract, 62: 336-342. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsap.13300